One of the things I talk with organizations about when they are considering agile is the way in which the culture supports teaming. Agile is intentionally light on processes and requires strong self-organizing teams to replace the externally governed processes of more traditional approaches. If you remove the processes without adding the teaming, you can get anarchy or total confusion. Neither of these is the intended outcome of agile.

One of the things I talk with organizations about when they are considering agile is the way in which the culture supports teaming. Agile is intentionally light on processes and requires strong self-organizing teams to replace the externally governed processes of more traditional approaches. If you remove the processes without adding the teaming, you can get anarchy or total confusion. Neither of these is the intended outcome of agile.

Most organizations will not admit that they are not supportive of self-organizing teams and in fact most pride themselves in strong teamwork, at least verbally. But when you ask the individuals on those teams how they feel about their level of autonomy, most will express quite the opposite. This is usually reflected through comments and actions that indicate a strong culture of cascading command and control with heavy oversight and micromanagement.

There are lots of qualities that make up high-performing teams, such as trust, transparency, commitment to a shared vision, strong communication, and comfort with healthy conflict. But one cultural norm that can undermine even the best work of a team is the lack of autonomy; a level of independence that is reasonably free from external influence and control. While the first set of qualities of high performing teams can be self-generated, meaning the team can themselves work on developing those characteristics, autonomy is to a large degree something that is granted or afforded external to the team, usually by higher levels of management and their associated leadership shadow.

Typically, while working with teams on items like trust, transparency and commitment, I also work with managers, executives and other stakeholders on creating and fostering a culture that truly supports teaming. Supporting and encouraging self-organizing teams is a scary proposition for most managers. Managers find themselves facing an interesting decision: “Am I willing to let go of some control in order to take advantage of the benefits associated with Agile?” The general feeling is that the people on those teams lack the expertise or experience, as well as the organizational purview, to effectively govern themselves, so they need some oversight. Unfortunately, this oversight usually comes in the form of prescriptive direction and control, stripping the team of their sense of self-determination and allowing them to abdicate responsibility for their success to the higher powers.

As parents, we know this feeling all too well. I felt this way when the girls first started driving and dating, when they went to college, and during most of the other new beginnings I felt I knew more about than they did. I still feel it when they enter new stages in their life — new jobs, marriage, a house, etc. There is a compelling urge to over-direct or control their behavior to avoid an outcome I believe they can’t perceive or anticipate. After all, I am their Dad (or manager) and that’s my job, right? Having lived more years than they, I certainly feel justified taking this position. The challenge with this view — whether with children or teams — is that until they develop a sense of autonomy, they will never develop a sense of responsibility.

Autonomy is scary from both perspectives. It is scary to allow and just as scary to accept. But it is necessary if teams and children are going to develop a sense of responsibility and ownership. When organizations start out on their agile journey they face the classic conflict of autonomy and control. They resist the typical command and control measures that are inherent in many traditional organizations while still being uncomfortable with the responsibility of autonomy. Self-organization is an elusive management concept. How can we organize something that is supposed to organize itself? How do we step into this space effectively?

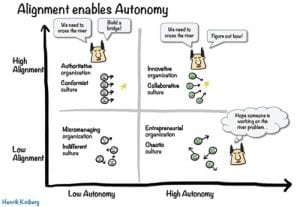

The counterpart to autonomy is alignment. Alignment is getting people to all pull in the same direction. Alignment is what enables autonomy. The stronger the alignment within the team, department or organization, the more autonomy you can grant, because you don’t have to worry that people are going in a million different directions.

What does this look like in practice?

The leader’s job is to communicate what problem needs to be solved and why, and the teams collaborate with each other to find the best solution. So top-down communication about where we are going, why we are going there, and what it looks like to be in that future state helps provide direction and purpose. Setting this direction with some guidance and organizational guardrails is what I call Guided Autonomy.

This term is actually borrowed from academia, where “flipped classrooms” allow students to decide their individual learning objectives while being guided by the teacher. In the Project Management and Agile simulation classes I deliver for Fissure, we don’t call ourselves instructors or teachers; we are guides. Each student comes to the class with specific learning goals. My job is to understand those goals and then guide them in achieving those goals. It isn’t traditional ILT (instructor-led training). It’s much better. Effective organizations frame autonomy and alignment as dimensions for developing high-performing teams. The goal is high autonomy and high alignment. The stronger the alignment, the more autonomy you can grant. Alignment enables autonomy. Alignment also allows you to measure progress toward the goals. Autonomy is achieved through the guided portion of guided autonomy. A simple matrix created from these two dimensions looks like this:

Low alignment/Low autonomy

In this state, people are treated as widgets and progress relies on continuous micromanagement. People don’t know how what they do contributes to the larger goals, or even what those goals are. Morale and personal investment in their work product is low. There is an indifference to their work because it has no motivational meaning to them. Classic mushroom management.

High alignment/Low autonomy

Under this paradigm, fear is the primary driver. People feel compelled to conform and align with those above them in the power chain. These cascading levels of control often have competing priorities at each layer. This can create latency in decision making that undermines the intent of the authoritative alignment itself. While there are situations where this autocratic approach can work, it can only be sustained through continual control. It is not self-sustaining because people have not bought in and therefore require regular management oversight. Teams may be doing the right things, but they are not internally motivated to do them well. Traditional command and control.

Low alignment/High autonomy

Organizations with low alignment and high autonomy can be highly entrepreneurial and for a while, a fun place to work, but usually only as individuals. These environments will also be chaotic. So, as the company grows, for the business to sustain itself, it will eventually have to align or die. In the chaos of lack of focus, teams will struggle to produce products and services that are sustainable. The natural tendency toward entropy will take over. By definition an organization exists for a collective purpose, but in these organizations the purpose is often unclear or diluted through things like unhealthy politics, mismanagement, hidden agendas or even being at odds with the people you hire. Teams may be doing things well, but they may not be doing the right things.

High alignment/High autonomy

People in self-organizing teams thrive on the self-centered elements of autonomy and mastery, but they also need alignment and an elevating sense of purpose. We all desire to be part of something larger than ourselves. In high autonomy/high alignment cultures, the job of managers and leaders is to help people make progress and make sure everyone’s on the same page about what progress looks like. They do this by providing guidance and support, and by making sure people have what they need without usurping autonomy with an autocratic style management.

Autonomy with alignment taps into the collective intelligence of the team, so people can come up with better solutions in a shorter time. It relies on transparency, clear processes and shared goals to define the boundaries of authority; and the greater autonomy promotes engagement and team learning. Autonomy is also incredibly motivating. People crave some degree of control and self-determination to produce innovative products rather than just doing what they are being told to do.

Agility requires a delicate balance of autonomy and control. Of course we put some limits on the exercise of autonomy both with our children and within the teams. Those limits are most appropriate when their actions could harm others, violate stated policies, or otherwise cause social disorder. But, for the most part, the things we tend to over prescribe as parents and managers are not life threatening. If we see our role as parents and managers as developers of potential, the fear of taking the risk will be less and the outcome may be well worth the experiment, but easier said than done.